How to Avoid Biased Survey Questions

Learn how to spot and fix biased survey questions. Get practical tips and real-world examples to improve your data quality and make better decisions.

Biased survey questions can completely torpedo your results by subtly nudging people toward certain answers. This is a huge problem because it leads to inaccurate data and, ultimately, bad business decisions. All because the feedback you collected wasn't what people really thought.

The Real Impact of Biased Questions

Have you ever filled out a survey and just felt like the questions were pushing you in a certain direction? It happens all the time. Even tiny choices in how you word a question can completely warp the outcome of your research. This isn't about getting slightly off numbers. It's about making big, expensive decisions based on faulty information.

The real danger here is that biased questions create a distorted picture of your audience. This distortion makes it nearly impossible for businesses to succeed at accurately identifying customer pain points and building products people actually want.

Imagine you're trying to figure out why customers are churning. If your survey asks, "How much did you enjoy our amazing new features?" you're probably not going to get a straight answer. By calling the features "amazing," you've made it awkward for users to disagree. They’ll likely give you the answer they think you want to hear, not what they really feel.

Why Seemingly Small Wording Choices Matter

This subtle influence can lead to some massive business mistakes. You might sink thousands of dollars into a feature nobody wanted or completely misread employee morale right before a wave of resignations. The data you collect is only as good as the questions you ask.

Let's break down the consequences:

- Distorted Customer Feedback: Biased questions can make a failing product look like a success or, worse, hide serious issues that need your immediate attention.

- Misguided Business Strategy: If your market research is built on a foundation of flawed data, your entire strategy could be heading in the wrong direction from the start.

- Wasted Resources: Acting on inaccurate insights means pouring time, money, and energy into solving problems that don't exist or building solutions that don't work.

- Loss of Trust: People can often spot biased questions from a mile away. When they do, it can seriously damage their perception of your brand's integrity.

The goal of a survey is to listen, not to lead. The moment your questions start guiding the respondent, you stop gathering insights and start collecting echoes of your own assumptions.

A Famous Polling Failure

History is filled with examples of what happens when surveys go wrong. The classic case is the 1936 Literary Digest poll, which famously predicted that Alf Landon would crush President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a landslide. Despite getting nearly 2.4 million responses, the poll was dead wrong. It called for a 57% victory for Landon, but Roosevelt won with 61% of the popular vote.

So what happened? This massive blunder was caused by a mix of biased sampling and poorly designed questions, proving that even a mountain of data is worthless if it's collected the wrong way. You can learn more about this and other survey disasters from this historical overview on Formpl.us.

This story really drives home the high stakes of survey design. The line between a question that subtly influences and one that outright manipulates can be very thin. Knowing that distinction is the first step toward crafting surveys that pull in honest, useful information. When you write truly neutral questions, you give people a chance to tell you what they really think, giving you the clarity you need to move forward with confidence.

Spotting Common Types of Question Bias

Recognizing bias is the first hurdle in eliminating it from your surveys. Biased questions often look harmless on the surface, but they’re packed with subtle cues that can nudge a respondent toward a specific answer. Once you learn to spot these patterns, you’ll start seeing them everywhere.

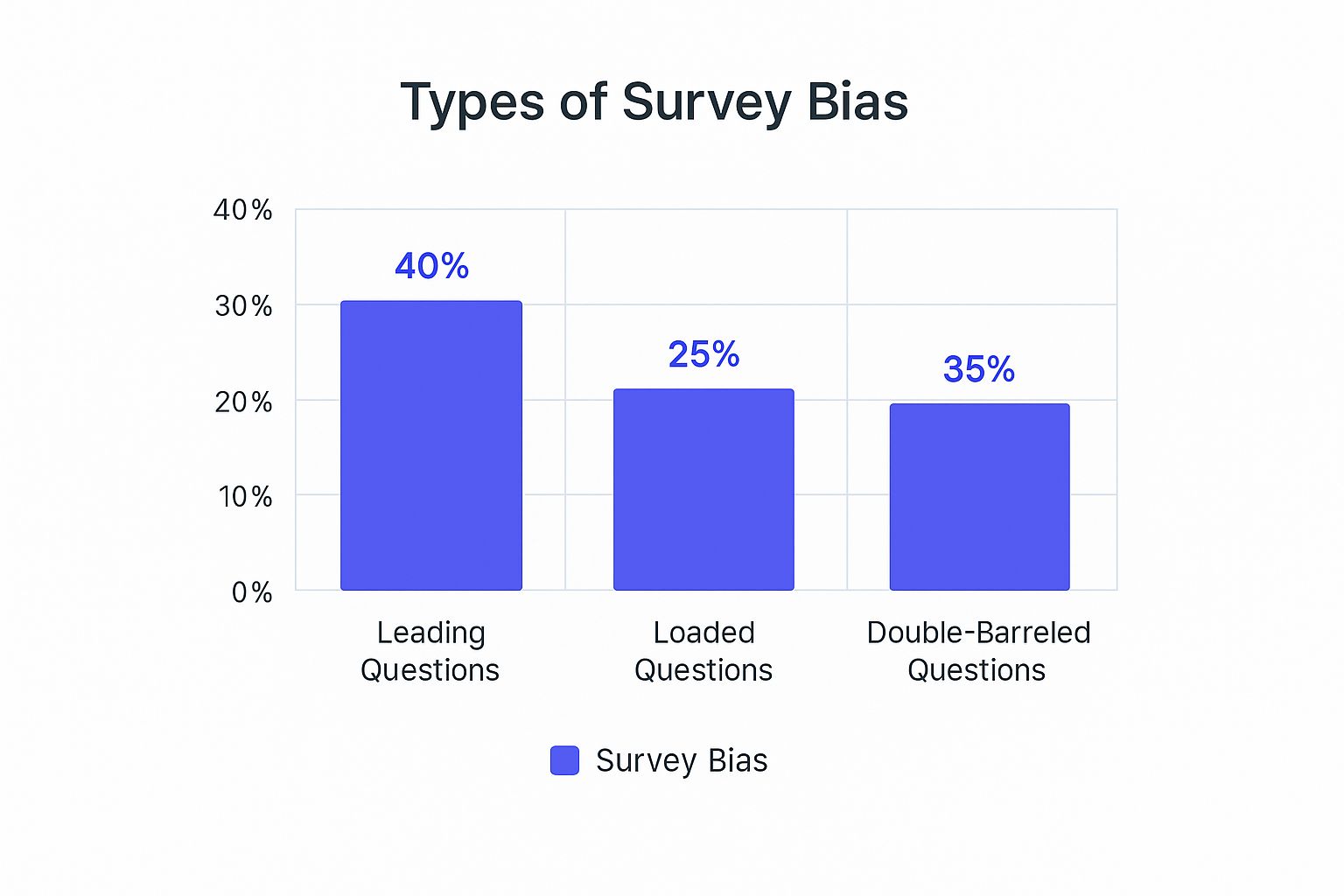

This infographic shows just how often some of the most common types of bias sneak into surveys.

As you can see, leading and double-barreled questions are the usual suspects, making up a huge chunk of biased inquiries. Let's break down these types with clear examples so you can catch and fix them in your own surveys.

Leading Questions That Nudge Respondents

A leading question is designed to prompt a specific response. It often contains suggestive language or presents an opinion as fact, making it hard for someone to disagree without feeling a little awkward.

Think of it like a lawyer in a courtroom drama asking, "You were at the scene of the crime, weren't you?" The question itself points to the answer they want.

Here’s a business example:

- Biased: "How much did you enjoy our award-winning customer support?"

- Neutral: "How would you rate your recent experience with our customer support?"

The first version uses "award-winning" and "enjoy" to frame the support team positively before the user can even respond. The neutral version strips out that subjective language and asks for a simple rating, leaving room for an honest assessment. If you're looking for more examples, our guide on avoiding bad survey questions offers a ton of additional insights.

Loaded Questions That Use Emotional Language

Loaded questions are a more aggressive form of bias. They come packed with emotionally charged words or assumptions that can make a respondent feel defensive, no matter how they answer.

These questions often touch on sensitive topics, trapping the person into confirming an underlying belief they might not even hold.

Consider this one:

- Biased: "Do you agree that our company should stop wasting money on useless team-building events?"

- Neutral: "How valuable do you find our company's team-building events?"

The biased question uses words like "wasting" and "useless" to paint the events in a negative light. An employee might feel pressured to agree, even if they secretly love the annual picnic. The neutral question removes the emotional weight and just asks for a straightforward opinion.

Double-Barreled Questions That Ask Too Much

Ever tried to answer a question that’s really two questions smashed into one? That’s a double-barreled question. They’re confusing and make it impossible to know which part of the question the person is actually answering.

This is one of the easiest mistakes to make, but thankfully, it’s also one of the easiest to fix.

- Biased: "How satisfied are you with our product's performance and user interface?"

- "How satisfied are you with our product's performance?"

- "How satisfied are you with our product's user interface?"

- Biased: "What is your favorite feature of our mobile app?" (This assumes the respondent even uses the mobile app).

- Neutral: "Do you use our mobile app?" (If yes) "What is your favorite feature?"

- Excellent

- Very Good

- Good

- Fair

- Very Satisfied

- Satisfied

- Neutral

- Dissatisfied

- Very Dissatisfied

- Phrase questions neutrally. Instead of asking for agreement, ask for a direct evaluation. Rephrase the question to something like, "How easy or difficult do you find our new user interface?"

- Balance your statements. If you absolutely have to use an agree/disagree scale, make sure you include a mix of both positive and negative statements. For instance, you could follow up the first question with another one like, "The new user interface is confusing at times."

- Start broad, then get specific. Think of it like a funnel. Ask about general satisfaction first before you start drilling down into specific features or recent interactions.

- Save sensitive questions for last. Anything personal, like income or demographic data, should always come at the end. By that point, respondents have already invested time in the survey and are much more likely to see it through.

- Randomize questions and answers. When you have a list of items (like asking users to rank features), randomizing the order for each person is a must. This helps cancel out primacy bias (where people favor the first options they see) and recency bias (where they favor the last ones).

- Instead of: "What are your perceptions regarding the efficacy of our onboarding protocol?"

- Try: "How effective was our onboarding process?"

- Ask for blunt feedback. After they take it, ask them straight up: Were any questions confusing? Did any feel awkward or seem to push you toward a certain answer?

- Look for red flags. Did almost everyone answer a specific question the same way? That might signal a leading question. Did a bunch of people drop off at the same spot? That question might be too confusing or sensitive.

- Time the survey. See how long it takes your test group. If it’s dragging on longer than you anticipated, you might need to trim it down. Survey fatigue is real, and it leads to rushed, low-quality answers.

- Were there any questions that felt confusing or could be read in more than one way?

- Did you feel like any of the questions were nudging you toward a specific answer?

- Was there anything you wanted to say but couldn't because an answer option was missing?

- Engagement level: Newbies, loyal regulars, and those who've gone quiet.

- Subscription tier: Free users, basic plan subscribers, and premium members.

- Company size: Small businesses, mid-market companies, and enterprise-level clients.

A user might love the performance but find the interface clunky. A single question forces them into a single, muddy answer. Splitting it gives you clean, actionable data for each part.

Questions Based on Faulty Assumptions

These questions assume something about the respondent that may not be true. They operate from a hidden premise, which can confuse or alienate the person taking the survey if that premise doesn't apply to them.

For example:

The biased version gives people no way out if they don't use the app. The corrected version uses a simple screening question first to make sure the follow-up is relevant. A small change that massively improves your data quality.

To make this crystal clear, here’s a quick-glance table comparing these common bias types.

Examples of Biased vs Neutral Questions

This table shows how a few simple tweaks can turn a biased question into a neutral one, giving you much more reliable data.

Fixing these is often about simplifying your language and splitting up complex ideas. Always read your questions back and ask yourself: "Am I making any assumptions here? Am I guiding the user toward a specific answer?"

Framing is everything. The way you present a topic can drastically change how people respond, even if the core question is the same. Small wording adjustments can produce wildly different results.

The power of framing was shown in a 2018 study that analyzed nearly a million survey questions. When people were asked about a hate group rally prefaced with “Given the importance of free speech,” 85% agreed to allow it. When the preface was changed to “Given the risk of violence,” only 45% agreed. That’s a massive 40-point swing based on wording alone. You can learn more about these powerful question wording effects.

How Answer Scales and Order Create Bias

It's easy to get so focused on question wording that you completely overlook another huge source of bias: the answer options themselves. How you design your response scales and the order you present questions can subtly nudge respondents, polluting your data before you even see a single result.

These design choices introduce biases that are often much sneakier than a simple leading question. Getting a handle on them is the key to collecting feedback that reflects what people actually think, not just how they reacted to your survey's structure.

The Problem with Unbalanced Scales

An unbalanced scale is just what it sounds like. It leans more heavily in one direction. It gives people more ways to express a positive (or negative) opinion, which can seriously skew your results by making one side of the argument feel more common or acceptable.

Think about a customer satisfaction survey with these answer options:

This scale offers three positive choices and only one that's remotely neutral-to-negative ("Fair"). A customer who had a perfectly average, forgettable experience might just pick "Good" because it seems like the middle ground, even if their true feeling is closer to neutral. This ends up painting an overly rosy picture of your service.

A much better, more balanced approach would be:

This structure gives you an equal number of positive and negative options around a true neutral midpoint. The result? A far more accurate read on how your customers really feel.

A neutral midpoint is your best friend. It gives respondents an "out" when they don't feel strongly either way, preventing them from being forced into a positive or negative choice they don't genuinely hold.

Acquiescence Bias and How to Fight It

Acquiescence bias, which I sometimes call "yea-saying," is our natural human tendency to agree with statements, no matter what they say. People just prefer to be agreeable, especially if they're not deeply invested in the topic. This is a classic problem with "Agree/Disagree" formats.

For example, if you ask, "Do you agree that our new user interface is easy to use?" you are almost guaranteed to get more "agree" responses than if you asked the question in a more neutral way.

Here’s how you can sidestep this:

This simple trick forces people to actually read and think about each statement instead of just defaulting to "agree" on autopilot. To really nail this, you should check out these great Likert scale examples for surveys that show you exactly how to build effective scales.

How Question Order Changes Everything

The sequence of your questions can create something called order bias. Questions you ask early on can frame the entire conversation, influencing how people answer everything that follows. You might also hear this called a context or carryover effect.

Let's say you kick off a survey by asking a user to recount a recent, frustrating experience with customer support. Their negative feelings from that memory are likely to spill over. When you later ask about their overall satisfaction with the product, their answer will probably be more negative than it would have been otherwise.

To avoid this, structure your survey with a clear, logical flow:

By putting some thought into both your answer scales and question order, you can minimize these hidden biases and get a much clearer, more honest picture from your survey results.

A Practical Guide to Writing Neutral Questions

Knowing how to spot bias is one thing, but the real skill is building habits that keep it out of your surveys from the very beginning. The good news is that crafting clean, neutral questions is a muscle you can build with a little practice. It all boils down to a focus on clarity, simplicity, and putting yourself in your respondent's shoes.

Think of this section as your practical checklist for every survey you create. Whether it's for customer feedback, market research, or employee sentiment, these habits will help you collect data you can actually trust.

Keep Your Language Simple and Direct

The best questions are almost always the shortest. You've got to cut through the jargon, corporate buzzwords, and any complex vocabulary that might trip up your audience. If a respondent has to stop and reread a question, you've already introduced a potential snag in your data.

Your mission is to make answering feel effortless. Stick to words everyone understands and frame your questions as directly as possible.

That simple switch makes the question accessible to everyone. You end up measuring their actual opinion, not their reading comprehension skills.

While the focus here is survey neutrality, the core principles of clear writing are universal. Anyone looking to sharpen their communication skills can get some great foundational advice from these Actionable Copywriting Tips for Beginners.

Focus on One Idea Per Question

This is one of the most common traps survey writers fall into: cramming two different ideas into a single question. We touched on this earlier with "double-barreled questions," but it’s so easy to do by accident that it's worth hammering home.

Before you finalize a question, stop and ask yourself, "Am I asking about one single thing here?" If there's any doubt, split it into two.

If a respondent could agree with one part of your question but disagree with the other, it needs to be two separate questions. This is non-negotiable for clean data.

A classic example is asking, "Was our support team quick and helpful?" The agent could have been very helpful but painfully slow to respond. By breaking it into "How would you rate the speed of our support team?" and "How helpful was our support team?" you get far more precise and useful insights.

Pre-Test Every Survey Before Launch

You will never catch all of your own biases. It’s just human nature. We're too close to our own work to spot the subtle assumptions we’ve accidentally baked into our questions. This is exactly why pre-testing, or running a pilot test, is a very important step.

Before you unleash your survey on your entire audience, share it with a small, diverse group of people who mirror your target demographic.

Here’s what you should be looking for during this pilot test:

This feedback loop is your best line of defense against launching a flawed survey. A quick pilot test with just 5-10 people can be the difference between a pile of useless data and a treasure trove of genuine insights. For a deeper look into the mechanics of question writing, our guide on how to write survey questions is a great next step.

By making these practices a routine part of your workflow, you'll consistently build surveys that capture high-quality, unbiased data. It's not about being perfect on the first draft. It's about having a process that catches bias before it can poison your results.

Of course, crafting perfectly neutral questions is a huge step forward, but honestly, it’s only half the battle.

A flawless survey can still produce terribly skewed data if you ask the wrong people or if only a certain type of person ends up responding. Bias can creep in long before a respondent ever lays eyes on the first question.

These external factors, like who you survey and how you reach them, are just as significant as the words you use. If you ignore them, you risk drawing the wrong conclusions, even with a brilliantly written questionnaire.

Sampling Bias: Are You Surveying the Wrong People?

Sampling bias happens when the group of people you survey doesn't accurately represent the larger population you want to learn about. It's one of the most common and most damaging types of survey error out there.

For example, let's say you want to gauge overall customer satisfaction. If you only send your survey to your most loyal, long-term customers, your results will naturally be glowing. This creates a dangerous echo chamber, completely hiding the reasons why less-satisfied customers might be churning.

You end up with data that confirms what you want to believe, not what's actually happening in the market. A complete view requires hearing from everyone: the fans, the critics, and those who are just plain indifferent.

A biased sample is like a funhouse mirror. It reflects a version of reality that is twisted and distorted, leading you to make decisions based on a reflection that isn't real.

Non-Response Bias: The Sound of Silence

Closely related to sampling bias is non-response bias. This sneaks in when the people who choose not to answer your survey are systematically different from those who do. Sometimes, the voices you don't hear can tell you more than the ones you do.

Think about it: people with very strong opinions, either extremely positive or extremely negative, are typically the most likely to respond to a survey. The silent majority in the middle, those with more moderate views, often just don't bother.

This can lead to a polarized set of results that completely misses the average user's experience. If you're only hearing from the happiest and angriest customers, you miss the nuanced feedback that often holds the most valuable insights for improvement.

How Historical Biases Shape Modern Research

These sampling issues are nothing new. They've been influencing data collection for decades, embedding biases into both historical and modern research. Skewed sampling and poor question design have led to some pretty big gaps in our collective knowledge.

A powerful example of this is the historical underrepresentation of certain demographic groups in safety research. For years, automotive safety tests primarily used crash test dummies based on the average male physique. The "female" dummies that were used often represented only the smallest 5th percentile of female body size, which skewed safety results and failed to protect a huge portion of the population. You can learn more about how this kind of systematic bias has impacted data collection for decades from this detailed report.

This just goes to show how assumptions baked into the research design phase can have far-reaching, real-world consequences. Creating an unbiased survey isn't just about question wording. It requires a thoughtful approach to your entire methodology. From who you decide to ask, to how you encourage a representative group to respond, and what hidden assumptions you might be bringing to the table.

Still Have Questions? Let's Clear a Few Things Up

Even after you've got a handle on the different kinds of bias, a few practical questions always seem to pop up. Let's walk through some of the most common ones I hear from people trying to get their surveys right.

What’s the Best Way to Stress-Test a Survey for Bias?

Your best bet is a pilot test, hands down. Before you launch your survey to the world, share it with a small, diverse group that mirrors your target audience. But don't just send it and hope for the best. Ask for their honest feedback when they're done.

I like to ask them a few direct questions:

This kind of direct feedback is gold. It catches the subtle stuff you'd miss on your own. Also, take a peek at the pilot data. If almost everyone gives the exact same answer to a question, it might be a red flag that your wording is leading the witness.

Is It Ever Okay to Use a Leading Question?

Honestly, for about 99% of surveys, the answer is a hard no. If your goal is to get untainted, honest data for market research, customer satisfaction, or employee feedback, you need to steer clear of leading questions. The risk of poisoning your data just isn't worth it.

The rare exception? A highly controlled user experience test. In that very specific scenario, you might intentionally phrase a question to test a very specific hypothesis about user behavior. But that's a specialized use case, not standard practice. For everyday surveys, neutrality is always your safest and most effective bet.

A biased question gets you the answer you want. A neutral question gets you the answer you need. Stick to what you need.

How Can I Reduce Bias if I Can Only Survey My Own Customers?

Working with just your own customer list is a common constraint, but you can definitely take steps to minimize sampling bias. The first and most important step is to be transparent about it in your final analysis. Make it clear that your findings reflect your current customers, not the entire market.

To get the most representative sample from your list, try a technique called stratified sampling. This just means you're dividing your customer list into meaningful segments and then sampling randomly from each of those groups.

For example, you could segment your customers by:

Doing this stops you from only hearing from your biggest fans and gives you a more balanced view from your entire customer base. But if you really want a true pulse on the market, you'll eventually need to look into a third-party panel to reach people who aren't on your list yet.

Ready to turn feedback into growth? Surva.ai gives SaaS teams the tools to create unbiased surveys, understand user behavior, and reduce churn with intelligent, automated flows. Stop guessing and start listening. Learn how Surva.ai can help you scale smarter.